Are you looking for some advice on how to stay warm and comfortable on spring and fall adventures? We can help.

This guide on layering for three-season camping will give you some handy tips on what to take – and why some materials might work better for you than others.

Layering for Three-Season Camping: Cheat Sheet

If you’re planning on spending a couple of nights under the stars in the spring, summer or fall, these are the basic layers you’ll need while at camp.

- Base layers (for torso and legs)

- Insulating layer

- Outer shell (rain jacket/wind jacket)

- For colder temperatures: extra protection for extremities (e.g. a warm hat, gloves and extra socks)

Dressing in layers gives you options for adding or removing layers based on current conditions so that you can stay comfortable on your adventures.

Layering for Three-Season Camping: Full Guide

1. Base Layer

A base layer is worn closest to the body and forms the ’base’ for your clothing layering system on your torso and legs. The primary function of the base layer is to wick away sweat and moisture. When in the outdoors, staying dry is key to staying warm and your base layer insures helps keep your skin dry and comfortable. Your base layer can also be insulating depending on the fabric weight and weave.

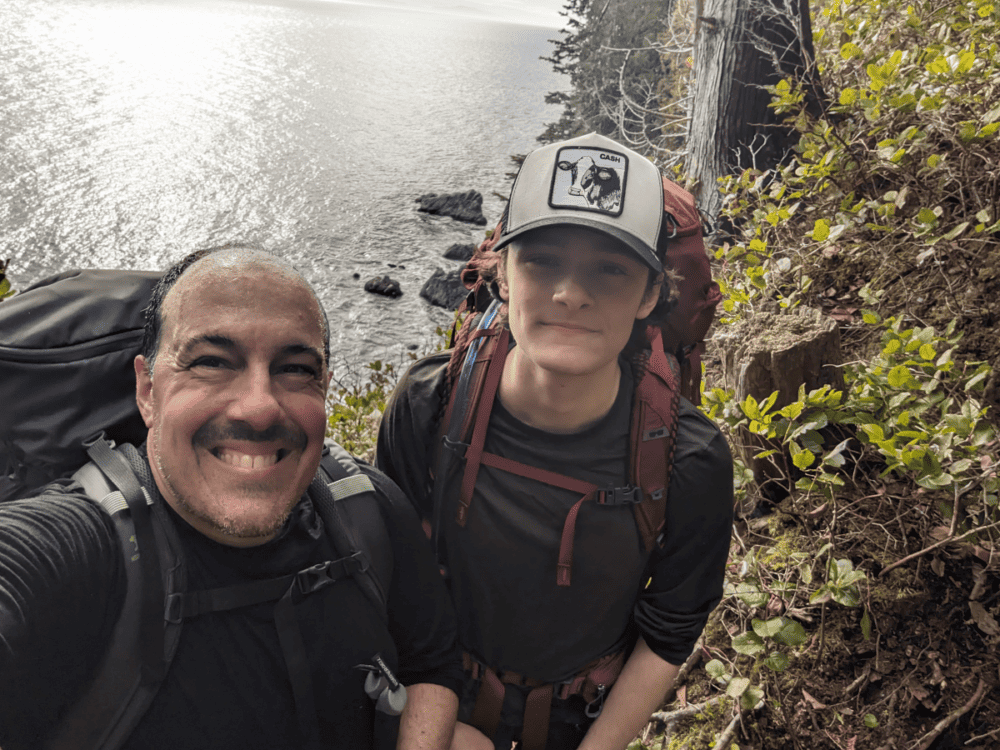

You might find base layers for your legs being referred to as ‘long johns’. These are great for use at camp (when you’re not hiking and your legs aren’t generating energy or heat). If you’re planning on hiking to camp in shoulder season and the temperatures are significantly chillier, I’d recommend taking some synthetic long johns to hike in as well. I just got back from backpacking the Juan de Fuca Marine Trail in B.C. and wore synthetic long-johns under my shorts on the rainy days to keep me comfortable.

Base layer materials

Base layers come in synthetic and natural materials and can also come in blended fabrics incorporating both synthetic and natural fibers. The most common synthetic materials are polyester and polypropylene, while the natural fiber category is now ruled by merino wool (which comes from merino sheep)l. It is absolutely essential to avoid base layers that have cotton fibers; cotton retains moisture and provides no insulation when wet.

I personally find synthetic base layers to be better at wicking moisture away, while merino wool is great for insulating. Consequently, I tend to wear synthetic bottoms and merino wool tops as my base layer on spring and fall adventures.

Base layers come in different weights (light, medium, and heavy) and also in different fabric weaves. Waffled weaves are better for insulation but can feel too warm during activity for me. Synthetic materials tend to retain odors, while merino wool can be refreshed by airing it out. The ideal combination of weights and fabrics is ultimately a personal preference, so use what works best for you.

2. Insulating Layer

Your insulating layer is used to keep you warm and can be changed out depending on the weather, your level of activity, and your personal susceptibility to getting cold. I tend to run warm and only wear insulating layers when my level of activity drops, like when I am hanging around the campsite.

Insulating layer options

Insulating layers work by trapping your body heat using synthetic on natural materials that incorporate air pockets into the insulating material.

Common insulating layers include a vest or sweater that uses fleece, wool, merino wool, , down, or synthetic insulation. .

Synthetic fleece, originally developed by Polartec and made from recycled plastic, comes in many options and weights. The pile of the fabric traps your body heat to keep you warm and also helps dissipate moisture from your base layer.

Wool sweaters are a staple insulating layer for many outdoor adventurers. While heavy, wool sweaters retain heat even when wet. Merino wool, which is lighter and softer, can be found in a variety of outdoor sweaters and vests.

Down and synthetic puffer jackets and vests have become extremely popular insulating layers for outdoor adventures. Puffer jackets leverage the loft of their insulation (which can be down or synthetic like Primaloft or Polartec Alpha). These items compress well and offer excellent warmth to weight ratio. Down tends to be a bit lighter and more compressible, while synthetic fill is lighter on your wallet and fares better when wet.

When outdoors in the spring and fall, I will often have 2 insulating layers with me; a thin fleece pullover and a down puffer jacket. These layers can be used either alone or together to prove the level of insulation I need for a given activity level.

3. Outer Shell

Your outer shell’s main purpose is to protect your legs and torso against wind and rain. While any shell made of synthetic material (like nylon, polyester, or vinyl) will block the wind, it is a shell’s ability to repel rain while allowing your own perspiration to escape that sets good shells apart.

The least expensive shells are waterproof but do not breathe (think yellow vinyl raincoats or ponchos). These still have a purpose for camping though; if you are going to be out in the pouring rain either camping or fishing and not moving a lot, having a truly waterproof layer has merits.

Jackets that are touted as being waterproof and breathable rely on either a DWR (durable water repellent) coating or membrane (or both) to allow one-way transfer of moisture. DWR coatings work by causing water on the outer layer of the shell to bead up and not ‘wet’ the material. Membranes, the most popular of which is GORE-TEX, have pores that are large enough to allow water vapor (perspiration) to escape, but small enough to prevent water droplets (precipitation) from entering.

Soft shells, introduced in the early 2000s and characterized by their apple and stretchy feel, offer superior breathability over their so-called ‘hard shell’ or traditional counterparts. Hard shells excel at being waterproof and often enhance breathability by adding ventilation zippers in the armpits.

If you run hot, as I do, you’ll probably find that your shell won’t breathe as much as you’d like, resulting in perspiration collecting on the inside of your jacket and making it feel clammy. My personal solution is to travel with 2 shells; one for active time that is more breathable, and one that is truly waterproof for down time at my campsite.

4. Your Extremities

Staying warm when camping doesn’t just come down to the clothes you wear on your legs and torso.

Keeping the extremities (like ears, fingers and feet) covered is really important to maintain warmth. A beanie hat, gloves and a spare pack of socks to sleep in should be essentials on your packing list if you’re planning on camping out on colder nights. Like the rest of your layers, avoid cotton and focus on merino wool or synthetic materials for these key items.